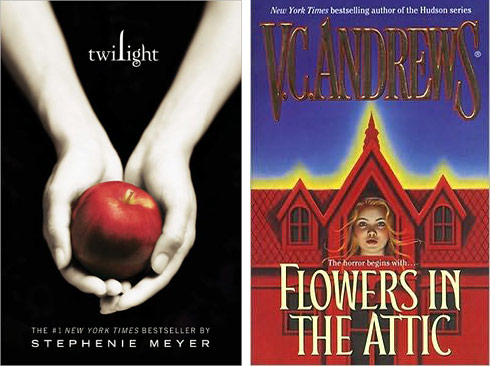

There’s a joke twittering around the Internet that pokes fun at Twilight and sequels, by characterizing them as a young girl’s tough choice between necrophilia and bestiality.

Zing! Though I never got around to reading Stephenie Meyer and her multi-volume vampire cycle, I absorbed enough, mostly from this Lucy Knisley cartoon, to get the joke. I’ve also picked up a few recurring complaints about the series over the years. I’ve heard people of the middle-aged variety saying the writing isn’t very good, the characters are about as deep as saucers, that the novels aren’t necessarily shining beacons of feminist literature. Also, the term “abstinence porn” came up.

(I rather like the sound of abstinence porn—it’s got rhythm. I feel as though someone should write a nursery rhyme or catchy jingle making heavy use of this phrase. Please let me know if you put one on Youtube.)

The criticism of Twilight may or may not be valid, but the sound of it is ever so familiar, because to my ear the complaining of we older, wiser, and more seasoned readers chimes along in perfect harmony with the things all the grownups were sayin’, twenty-some years ago, when I and my friends were nose-deep in V.C. Andrews’s Dollanganger Saga. This was, you may recall, a five-book series that began with Flowers in the Attic in 1979. The first book covers the childhood of two ill-fated lovers, Cathy and Christopher Dollanganger. Novel after novel followed this duo, through abuse, maimings, miscarriages, fatal fires, and other miseries, until both of them and V.C. Andrews had passed away. Even then the story lurched on, circling back to its beginnings with an 1987 ghost-written prequel, Garden of Shadows.

Flowers in the Attic and its sequels have only the faintest whiff of a paranormal element: in times of crisis, Cathy has prophetic dreams. It was neither ghosts nor creeping Lovecraftian entities that were the source of the horror generated in these books, but rather a more Poe-like Gothic sensibility. The Dollanganger saga is about the persecution of innocent children by immensely cruel and powerful adults. It’s about love betrayed, and the way that betrayal warps people who might otherwise be good and content. It’s about the sins of one generation being compounded, viciously, in the next. These are not books about monsters that come from laboratory experiments, outer space or disturbed baby graves. They’re about the evil we find close to home, the interior rot that some of us really do spread, plague-like, to others.

(Communicable evil. Hmmm. That edges us back towards the sparkly vampires and lycanthropy, doesn’t it?)

The Dollanganger story begins with an idyllic nuclear family, headed by mom Corrine and dad Christopher, who love their four kids to pieces. Unfortunately, there’s something they love even more, and it’s their credit cards. When Dad is killed in a car wreck, the debts make it utterly impossible for Corrine—whose chief job skill is being decorative—to support her family. She throws herself on the mercy of her parents, a pair of religious fanatics with millions in the bank.

Those parents. They tossed her out years ago. Disinherited her, too. Because she eloped! With her father’s half-brother, no less! So unreasonable.

Anyway, the grandparents do accept Corrine back into the fold, sort of. She brings the children to Foxworth Hall, slips them into an upstairs bedroom, and introduces them to her thoroughly terrifying mother. The women then tell the kids that Grandpa has to be softened up a little before anyone breaks it to him that his once-beloved daughter and not-so-darling brother had a brood.

Once they’re up there, locked away in a quiet wing of the house, they stay there for an extremely long time.

How does a series whose main characters are confined to one room and a big attic end up being so compelling that it’s not only still in print but it had a hold queue in my local library? Is it the writing? No. It’s very overblown, with lots of romantic flourishing and an “Oh!” on every other page. The characterization? Nothing special there either, although the prickly distrust between the adolescent Cathy and her mother does ring very true at times. Why did teen girls, me included, hoover these up like there was no tomorrow? Why are they all over Twilight now?

Well, of course, there’s all that sexual tension. The appeal of erotica, I assume, doesn’t need explaining.

Some part of our “Why this, of all things?” refrain is probably unanswerable unless you are, in fact, a young adult. (And if you are, then you know, okay, and you don’t need the answer.) But heck, I’ll take a stab at it: when you get past the age where you’re capable of believing there’s something carnivorous and hairy under the bed, you don’t then lose your capacity for fear. The monsters go, and in their place, lucky you, you get to start imagining real calamities: losing your parents in a car wreck, becoming destitute, having someone you love turn on you, or doing something so shocking that the community ostracizes you.

What’s it like to experience violence, imprisonment, sexual assault? These are questions that become vitally important to girls as they become more independent.

Assuming you’re lucky enough to have had a reasonably non-harrowing childhood, you go through a stretch of development after the belief in magical creatures wears off and before you’ve had a chance to hone your threat-assessment skills in the real world. Fiction bridges the gap by letting readers experience the unthinkable. Gothic fiction, with beatdowns from Grandma and weird, porny not-quite-rape scenes and poisoned pastries, lets us experience the unimaginable in the literary equivalent of 3D and surround sound, with the emotional intensity cranked to MAX.

What does Flowers in the Attic have? There’s the spooky house, for one thing. There’s the money-can’t-buy-you-love moral lesson, embedded in the tantalizing prospect that the four little shut-ins will one day be filthy rich, if they can just keep their grandfather from finding out about them. There’s the grandmother, who’s every bit as scary as Dracula. There are whippings, starvation, attempts to disfigure the kids, and daily reminders that the four of them are inbred Devil’s spawn. There’s mouse-eating and child-death, revenge, forgiveness, and…um…brother-sister incest.

Cathy and Christopher begin as innocents, but as soon as they meet Grandma, they’re treated to her certainty that they are lustmonsters, primed and ready to follow in their mother’s uncle-marrying footsteps. This seems pretty paranoid when Cathy is only twelve, when they’re initially locked up. But as she and Chris are forced to pass through adolescence in close proximity, with nobody else to turn to, as they are made to rely on each other as a couple does, as they take on a parental role in raising their younger siblings, sexual feelings do, inevitably, arise.

The abstinence porn factor in Flowers in the Attic doesn’t get drawn out for nearly as long as it does in the Twilight books. There’s a bit of that, to be sure, but Chris doesn’t have the restraint of an Edward Cullen.

A few weeks ago, you might recall, I laid out some pretty hefty complaints about the sex scene in Stephen King’s It. And what I learned from Tor.com visitor comments was that the scene was a deal-breaker for many, many readers besides myself. So here’s a bit of a poser: I argued that King’s otherwise lovely and nuanced horror novel failed at the point where the Losers’ Club in It has a big ol’ consensual gang bang with Beverly.

Yet in Flowers in the Attic, which is inferior to It in innumerable ways, the sick sex scene works.

Why? For one thing, Cathy and Chris aren’t OMG, ten years old! For another, they damn well know they shouldn’t. They’re set up to fail, but they fight the urge before and they regret it bitterly afterward. They don’t have a particularly good time losing their virginity… it’s not some multiple orgasm extravaganza. There’s no romantic love payoff, either. Finally, the experience leaves Cathy all messed up when it comes to things like good, evil, love, lust, and the religious faith that is part of what’s sustaining her through their long imprisonment.

Andrews, quite simply, had a better grip on women and sex. I wouldn’t go so far as to call this series emotionally honest, and I’m not saying the Chris/Cathy scene mirrors everyone’s first time—that would be awful, and cynical, and untrue. But the messiness of Cathy’s attitude to sex and the way it ties into her years of abuse does have an odd veracity to it. Is it because Andrews, being a woman, had a better grip than King on what female readers would believe? And be scared of? Probably, yes.

These books aren’t great, and they don’t hold up to critical scrutiny. But they do entertain. They do so by inflating and sensationalizing the very real and very primal fears of young readers, and specifically of women stepping out to claim their space in a world that they know, perfectly well, isn’t entirely safe or welcoming.

Is it the same with Stephenie Meyer? You’ve read her—you tell me.

A.M. Dellamonica has a short story up here on Tor.com—an urban fantasy about a baby werewolf, “The Cage” which made the Locus Recommended Reading List for 2010.